The global tax landscape has reached a definitive point of no return. The OECD’s comprehensive framework on Digital Continuous Transactional Reporting (DCTR) is far more than a technical guideline; it is the strategic blueprint for Tax Administration 3.0. This era represents a fundamental shift in fiscal governance, characterized by the seamless integration of tax compliance into the natural digital ecosystems of business activity. We are witnessing the end of manual, retrospective reporting and the birth of an automated, real-time fiscal reality where the tax authority becomes a silent, digital partner in every transaction.

To navigate this transition, enterprises and policymakers must look beyond the mechanics of electronic invoices and master the strategic pillars that will define international trade and fiscal policy for the next decade.

1. Navigating Global Proliferation and the Risk of Heterogeneity

The rapid, “uncoordinated” expansion of DCTR mandates is the most significant structural risk to the modern global economy. While jurisdictions design these regimes to solve domestic VAT gaps—the difference between expected and actual tax revenue—the result is often a fragmented landscape of “digital islands.”

Figure 1. Visual summary of the six key areas of considerations for DCTR design and operation:

- The Strategic Conflict: Multinational corporations and SMEs alike are struggling to survive a patchwork of wholly distinct national regimes. The compliance burden of maintaining different technical connections for every jurisdiction is becoming unsustainable.

- The Path Forward: International consistency is no longer optional. Jurisdictions must move beyond isolated domestic interests to adopt common standards. Mitigating legal uncertainty and high operating costs requires a commitment to “technological neutrality” and the adoption of shared schemas such as OASIS UBL or UN/CEFACT. A single technical investment by a business should, in theory, serve multiple markets, turning a compliance hurdle into a global trade enabler.

2. The Architectural Fork: Invoice Transmission vs. Data Transmission

A fundamental policy decision for any tax authority is the choice between two overarching DCTR models: full electronic invoice transmission or a subset of transactional data reporting. This choice fundamentally changes how data flows between businesses and government, shifting from periodic batches to real-time streams.

- High Intervention (Clearance/Invoice Model): This model offers the highest level of fiscal assurance as the government involves itself directly in the commercial invoicing process. The invoice is essentially “cleared” by the tax authority before it becomes legal. However, the trade-off is a potential “Single Point of Failure”; government system downtime can paralyze private commerce, creating massive economic bottlenecks.

- Organic Flow (Reporting/Data Subset Model): This approach builds more organically on existing commercial data flows. It allows businesses greater flexibility but may provide tax authorities with less granular data for real-time risk assessment.

- The Resilient Balance: The OECD report suggests that the most successful systems are those that strike a balance—leveraging existing commercial standards while ensuring the data subset is sufficient for robust compliance without over-engineering the process.

3. Interoperability and the Strategic “Five-Corner Model”

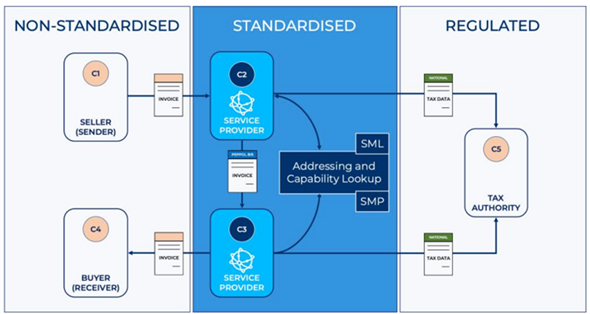

For DCTR to be sustainable, it must be interoperable with the diverse ERP, accounting, and billing systems used by modern businesses. The Five-Corner Model has emerged as the architectural answer to this challenge, facilitating the transition from a centralized to a decentralized, interconnected network.

- Maintaining Autonomy: In this model, the Seller (Corner 1) and the Buyer (Corner 4) maintain their internal systems, while Service Providers (Corners 2 and 3) handle the complexities of formatting, validation, and transmission. The “Fifth Corner”—the Tax Authority—receives the reporting data through these interoperable hubs.

- Standardized Connectivity: By adopting this model, jurisdictions ensure that real-time reporting does not require businesses to “rip and replace” their existing infrastructure for every new mandate. It allows for a “Connect Once, Comply Everywhere” approach, which is vital for the scalability of digital trade.

4. Protecting the Growth Engine: Mitigating the SME Burden

DCTR compliance costs—ranging from heavy IT infrastructure investments to constant procedural updates—fall disproportionately on Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). If not managed with care, Tax 3.0 could inadvertently become a barrier to economic growth and entrepreneurship.

- Relief Strategies: Jurisdictions must implement specific measures to protect smaller economic operators:

- Free Government Portals: Providing no-cost, basic tools for low-volume taxpayers.

- Limited Data Requirements: Restricting mandates to standard accounting fields already present in basic software packages.

- Gradual and Tiered Phasing: Implementing mandates based on turnover thresholds, allowing smaller actors more time to observe, learn, and adapt.

5. Information Security and the Doctrine of Data Minimization

As tax authorities gain real-time visibility into the “circulatory system” of the economy, the surface area for cyberattacks increases exponentially. While adhering to ISO/IEC 27000 standards is the baseline, the ultimate strategic defense is Data Minimization.

- The Trust Mandate: By collecting only what is strictly necessary to verify tax liability, authorities reduce the risk profile of the data they hold. This strategy is the primary driver for building institutional trust. In a digital-first world, trust is the currency of compliance. If businesses fear their competitive trade data or sensitive pricing is at risk, the entire DCTR ecosystem loses its legitimacy and becomes a point of political and economic friction.

6. DCTR as a Catalyst for Economic Modernization

The transition to Tax Administration 3.0 is not merely an enforcement tool to tackle VAT fraud. It is a catalyst for the digital transformation of the entire economy, moving the needle on national productivity.

- Beyond Enforcement: When DCTR is designed with a vision beyond revenue collection, it forces a long-overdue “cleanup” of corporate master data and encourages the adoption of digital processes across all sectors.

- Economic Benefits: High-quality, real-time data allows for more accurate economic forecasting, faster VAT refunds (which directly improves business liquidity), and a drastic reduction in the “shadow economy.” DCTR is the infrastructure upon which a modern, transparent, and hyper-efficient digital economy is built.

Final Critical Take: From IT Upgrade to Change Management

The move to Tax 3.0 is inevitable, yet the missing link in many implementations is not technology, but Change Management. Jurisdictions and enterprises that view DCTR solely as an IT upgrade are destined to fail.

The most successful regimes will be those that view it as a total redesign of the “customer experience” of tax. In this vision, the government becomes an invisible, integrated partner in commerce, and compliance becomes a seamless, automated byproduct of doing business. For the modern enterprise, the goal is clear: transition from “reporting the past” to “managing the present” through a robust, interoperable, and secure digital tax strategy.